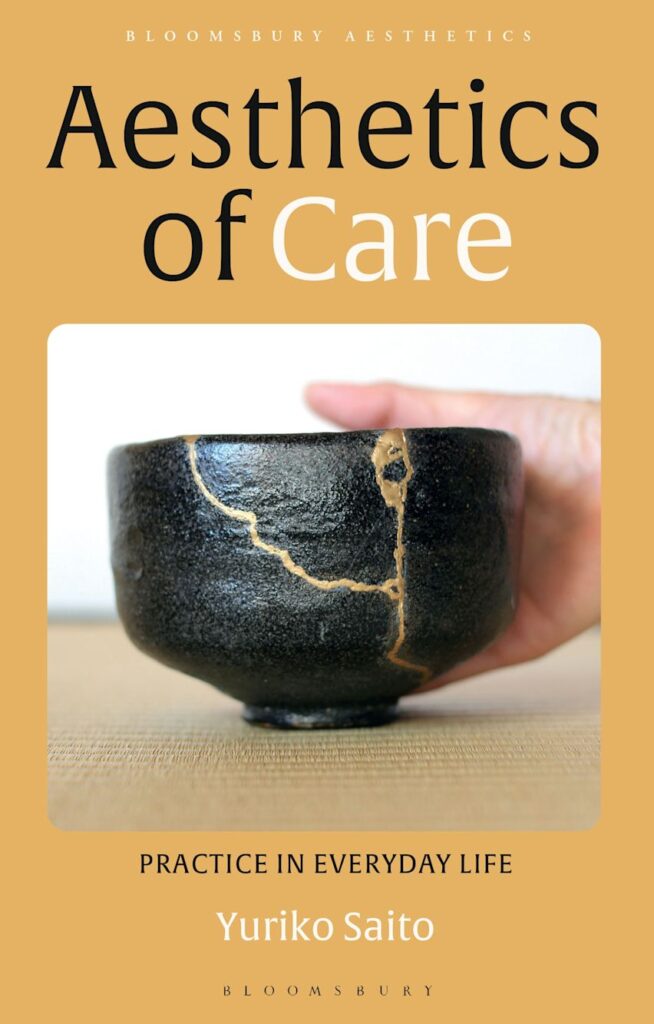

Aesthetics of Care; practice in everyday life (2022) Yuriko Saito

The central argument of this book is that in everyday life aesthetic sensibility and ethical concerns are intimately connected and interdependent and “intertwined”. Saito essentially claims that care is an aesthetic practice insofar as it is part of the everyday attending to the body, material technologies and others, including non-human animals. In short, care is the ethical and aesthetic “mode of being in the world” (p.2) In fact, this general conception of aesthetics is regarded as immediate in one’s quality of life. Thus, while Saito’s approach challenges a Cartesian Dualist approach, it maintains the Kantian Enlightenment synthesis of the ethical and the aesthetic and does so in a way from a Virtue Ethics (and specifically virtue aesthetics) approach combined with a Japanese aesthetics emphasis on “self-cultivation and self-discipline” in aesthetic experience. There is a sustained emphasis on attention, patience, openness, silence, disinterestedness, and the cultivation and nurturing of a moral educational journey yet we know of competing virtues in aesthetics and particularly art practice such as authenticity, originality, currency, restrictions, criticality, and even righteous anger, etc that are overlooked. The risk is that Saito, in overplaying the similarities of the ethical and the aesthetic (in Chapter 1) has simply subsumed the latter into the former. Equally, the risk is that the term care becomes an empty repository for all that is virtuous. “Care begets care” (p. 7) she proposes but care can also beget its opposite. It can beget carelessness, abuse, being taken for granted, etc. Care can be unwanted, unnecessary, and even unhelpful. Care is not a one-way-street and there is at least a recognition of the need for self-care as care can be onerous, even dangerous, for the caregiver (p. 62), and that reciprocity is an essential requirement. Yes, care may entail putting your seat belt on first but weather to buckle someone else up requires practical wisdom and necessarily entails risk.

Care usually entails an opportunity cost, i.e. to care for something is to not care for other things. A greater consideration of art may have teased out this problem of care. After all the curator, the conservationist, and the artist alike know the cost of their time. Even if we are to emphasise the relational nature of aesthetics there is a necessary limit to the relational features we can appreciate. There is, it could be said, a potential virtue of ignorance in aesthetic experience. If there were not the idea of “spoilers” would not exist.

While there is a central recognition of relational nature of design and aesthetics (Bourriaud in the context of contemporary installation art and Berlant in the context of environmental aesthetics etc.), there is an absence of any discussion of politics per se (Rancière, for example, is listed in the bibliography but not referenced elsewhere). The “refined aesthetic sensibility” (p.18) envisioned is not going to be available to all equally. Politics is most glaringly overlooked in chapter 3 when Saito discusses the role of embodied, artistic, and social aesthetics. Who gets to curate, what bodies get to have aesthetic experiences, and the geography of beauty/ AOC, some appealing manhole covers, user-friendly designs and hostile public architecture are included, are well-established concerns that would be worth including. Anti-homeless spikes depending on one’s ideology, after all, could be described in the language of care. Is there in Rancière’s language a distribution of (an aesthetics of) care? For example Christine Milligan writes of proximity and distance when she describes “Landscapes of care” (2010).

An implication of this oversight is the emphasis, inspired by debates in virtue aesthetics (Roberts, Woodroof, Goldie, Kieran etc.) on the intention of the maker at the expense of the material and production politics of the object’s creation. While noted that care work, for example, cannot be entirely done begrudgingly, overlooked here are the class and gender inequalities of the “aesthetic labour” of such work.

Given the stressful emphasis on productivity and capitalist efficiency, there is a general neglect of stillness and attentive concentration that Saito could be seen to address. An AOC can thus rightly be seen to refocus on and connect with beauty in the everyday together. This can simply entail sharing images or sounds you find appealing. The ubiquity and accessibility of beauty after all make it easy to ignore. An emphasis on care can rightly remedy this.

The book is strongest, I believe when taking from aesthetics an emphasis on the appreciation of objects, the idea that treatment of objects is equally ethical (Chapter 4), andthe virtue ethics insight that “there is no “one-size-fits-all” mode of expressing care” (p. 27). Expanding on the latter point it is clear that the aesthetics of care, like an ethics of care is not a solitary activity. Rather it is durational, collective, interdependent (Chapter 3) and relational (Chapter 2) activity. Despite my criticism concerning the politics of aesthetics of care, this is a rich book that introduces many if not most of the concerns of AOC and the current literature on the topic.

Connell Vaughan

TU Dublin

Saito Yuriko, Aesthetics of Care; practice in everyday life. London: Bloomsbury 2022.

ISBN:9781350134188